Short version for longer version see here

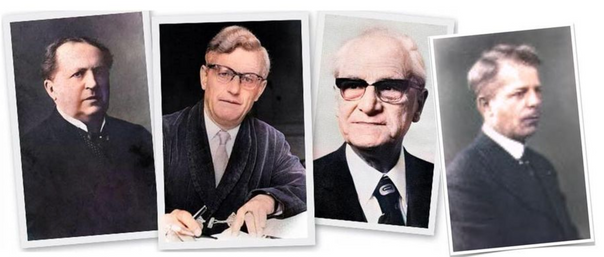

Dooyeweerd, Vollenhoven and Janse are often thought of as the forerunner of Reformational philosophy. These Dutch philosophers developed ideas from the Reformed theologian and Christian Democrat premier, Abraham Kuyper, into a robust, integral, systematic Christian philosophy. Confessing that the lordship of Jesus Christ covers every area and aspect of life, it sees no area of life as religiously neutral – and all as susceptible of redemption. Several main themes structure Reformational thought. They include:

An Emphasis on God’s sovereignty

Abraham Kuyper famously said: ‘There is no square inch in the whole domain of human existence, of which Christ, the sovereign Lord of all, does not say, “Mine”.’ Across the spectrum of life and culture, Reformational philosophy is motivated to assert the lordship of Christ in scholarly fashion. History, philosophy, theology, business, politics, mathematics, art, the sciences: as human work, all can undergo inner reformation.

Sphere sovereignty

Following Scripture, Kuyper acknowledged that ALL authority has been conferred on Christ. No human authority, wherever it is exercised, is original or total, but always: delegated and specific. Kuyper’s theory of sphere sovereignty recognises diverse, independent, interwoven spheres in human life – and God sovereign over them all.

Norms for church-life differ from norms for business. Office held in one doesn’t carry over into the other. Church shouldn’t be run as business nor business as a church.

Cultural mandate

Kuyper’s square inch quote embodies the cultural mandate of Genesis 1:26-28 and Genesis 2:15. This “subdue, rule, till and keep” is a command to develop culture, to unfold potentialities latent in the good cosmos God created. It must express Christ’s kingdom everywhere; no area is exempt. It implies that the good creation can be opened up, given added value; the garden becomes a strikingly beautiful city.

Common grace

Through common grace shown to creation as creation, that dominion over nature mandated before the fall can be realised after it. Common grace has a twofold effect: it curbs the effects of sin and restrains the deeds of fallen humanity; it also upholds the ordinances of creation and provides the basis for Christian cultural involvement; common grace provides the foundation for culture. The cultural mandate to develop and fill the earth was not rescinded after the fall into sin. Therefore, cultural withdrawal is not an option for Christians.

Antithesis

The kingdom-rule of God is everywhere contested by the parasitic rebellion of Satan. A cosmic, spiritual struggle rages even within an individual believer’s heart! A common commitment to Jesus Christ marks out the people of God, but this is no private and individual matter. Living in the world, they are not willingly ruled by the world’s values. A difference in worldview attaches to their hold on Christ. Principles diverge. There is a noetic (relating to knowledge) antithesis between those who start with submission to God and those who do not.

This is, in part, one reason for Kuyper’s advocacy of other Christian institutions than the church. A Christian political party has different starting-points than one based on naturalistic lines. Different foundations require different out-workings. Commitment to Christ can’t be accommodated to naturalism or any other non-Christian philosophy.

Church as institute and as organism

Kuyper used these metaphors to illustrate an important distinction in our experience. As institution, the church is organisation, sacraments, ministers; as organism it invades the world: Christians, the body of Christ, at work in society, strengthened and served by the church as institute. The church as institute does not run schools, universities, coffee shops or trade unions; the church as organism may. For Kuyper, church is not just about Sunday services or missions; it has every facet of life and culture to reform.

For the church to be truly both institution and organism, the role of the institutional leaders must be to equip the church as organism to do works of service in the marketplace, the classroom, business, politics, laboratory and so forth.

Modal aspects

To describe the observed unity and diversity of reality, Dooyeweerd identified fifteen different modal aspects. They can be detected in the apparently simple job of buying a bottle of whisky. A theologian asks why Christians buy and drink alcohol and Muslims don’t. An ethicist asks why I buy fair trade whisky. A jurist knows where it is legal to buy whisky, and when. An aesthetics expert is taken by the size and shape of the bottle, the colour of the whisky, the way it is packaged. The economist is primarily interested in the demand for, and cost of, whisky. A sociologist looking on will consider the impact of alcohol on society and she observes the interaction between the shopkeeper and me. The ways of communicating between customers and the shop keeper are noticed by the linguist. Psychologists might think about what drives me to want a tot of whisky and what motivates the shopkeeper to please me. Different academic disciplines reflect the modal aspects and each can appeal to the different kinds of lawfulness displayed. Clusters of laws discerned within, say, the field of economics lead Dooyeweerd to describe the modalities as law spheres.

The bottle of whisky itself also has several aspects: their number is inventoried each week; they take up a certain amount of space; the whisky inside can be described with chemical formulae, the bottle stays on the shelf because it obeys Newton’s laws of motion, the contents predictably modify circulation and consciousness. Natural science is concerned with these numerical, spatial, kinematic, physical and biotic modes; they are the fields of its investigation.

Not only do scholars investigate different fields of behaviour, the scientific pursuit itself is governed in irreducible ways by each different law-sphere. The universal interplay of law-spheres gives us a vitally important means of structural analysis of every entity or event:

Sensitive: The impressions received from sense data, and psychological factors are obviously important considerations for the practice of science.

Analytical: Analysis is essential to science; it is needed to distinguish between competing theories and hypotheses.

Cultural/ historical: Science is performed in a particular cultural milieu and context; it cannot be divorced from it; it builds a lasting edifice.

Lingual: Science has its own symbolism: e.g. H2O. Research results are communicated through specialist journals or conferences. Their language is often unintelligible to non-experts in the specific field.

Social: The importance of the community of scientists to the advance or retrenchment of science has been shown by Kuhn. Similarly, Polanyi talks about a community of explorers.

Economic: Funding restraints mean that scientists must choose their research carefully to have a chance of securing it. Very often it is: no money, no science.

Aesthetic: The beauty and simplicity of a theory is one criterion for its validity.

Juridical: Scientists have legal responsibilities and should not break the law no matter how important their research. They must not plagiarise.

Ethical: As well as legal standards there are moral criteria they must recognise. Should animals be used in research, should untested genetically engineered organisms be released into the environment, should we clone humans? These are all ethical issues that confront the scientist.

Faith: Polanyi, like Dooyeweerd, has shown how important faith is to science.

Idolatry

Dooyeweerd’s modal aspects reveal much about modern idolatry: the -isms. Idolatry is probably at play when one or more of them is given a priority over the rest. Marxism, for example, overemphasises the economic aspect, materialism the physical, radical feminism the biotic, rationalism the logical and so on.

Contemporary idols are not things we put on the mantelpiece; they tend to be ideas or concepts rather than objects. Think of: economic growth (at all costs); material prosperity; exam success; family; nation; the idea that science and technology will solve all our problems; the list is almost endless.

Idolatry comes from our being worshippers: we are created with a need for worship. Be we Christian, Buddhist, new agers, modernist, postmodernist, agnostic or atheist, we can’t escape it; it’s the way God made us. There may be no public or ceremonial aspect to our worship, but it is worship nonetheless. Anything that’s taken to be “just there”, (a non-dependent reality on which the rest of reality depends like matter, number or logic) is thereby given the status of divinity according to the reformational philosopher, Roy Clouser.

Dualism

One of the biggest problems for Christians who want to develop and embrace a biblical worldview is dualism: we tend to split life into two structural levels, higher and lower and to blame the lower (and not ourselves) for the world’s evils. Examples are sacred / profane, spiritual / secular, grace / nature. Reformational thinkers see creation as integrally comprised in God’s purpose of redemption and restitution.

Structure and direction

The structure/ direction distinction is an important insight. Structure refers to the modal make-up of created things; direction refers to the pull of sin or grace on it. In fall and redemption, only the direction and not the structure of creation has altered.

Ground motives

Dooyeweerd identified four religious dynamics that have shaped the development of Western culture. These ground motives are 1) form-matter (Greek); 2) nature-grace (Mediaeval); 3) nature-freedom (Enlightenment) and 4) creation-fall-redemption (Biblical Christian). The first three are ‘internally dualistic and fragmentary.

Taken from Bishop, Steve 2019. Reformational philosophy – an introduction