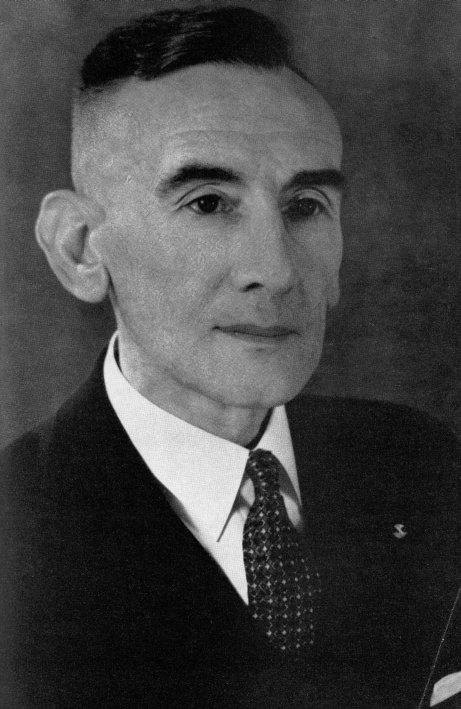

Johan Peter Albertus Mekkes (1898-1987) was one of the second generation of reformational scholars. He studied under Herman Dooyeweerd and became a leading figure in reformational philosophy after World War II. He is little known in the (1898-1987) was one of the second generation of reformational scholars. He studied under Herman Dooyeweerd and became a leading figure in reformational philosophy after World War II. He is little known in the English speaking world due to a lack of translated works. Nevertheless, he was influential on a number of younger scholars whose work is more widely known.

Life

From 1915-1940 Mekkes was a high ranking officer in Dutch army. In 1928-1931 he studied at the Advanced Military Academy in The Hague before becoming an adjutant to the commander of the field army (1933-1940). After studying law at the Roman Catholic University in Nijmegen, he received his doctor’s degree under Dooyeweerd in 1940, which elaborates Dooyeweerd’s approach to the humanistic theory of the law-State .[1] From 1942-1945 he was imprisoned by Nazis in Stanislau POW camp. There he introduced the thought of Herman Dooyeweerd to Hans Rookmaaker giving him a copy of De Wijsbegeerte der Wetsidee to study.

From 1945-1975 he worked for Dutch equivalent of the FBI. In 1947 Mekkes was one of the first four philosophers (the others being K.J. Popma, S.U. Zuidema and Hendirk van Riessen) to be appointed by the Association for Cavinistic Philosophy to a philosophy chair at different state universities. Of Mekkes work at the time Bernard Zylstra writes “After his appointment at Leiden and Rotterdam, Mekkes published regularly but not extensively, directing his penetrating analysis to the fabric of western culture and its cohesive force, reason” (Contours of a Christian Philosophy p.24)

Thought

Mekkes is often described as having been one of Dooyeweerd’s most faithful defenders, but also as having developed a unique style and approach which in some way could be seen as having a critical relation to Dooyeweerd’s thought. His article ‘Wet en subject in de Wetisdee der Wijsbegeerte’ (1962) reviewed the criticisms of Dooyeweerd made by Conradie, Brummer, and Van Peursen and defends him on the concentration point, supra-temporality, and his transcendental critique. Nevertheless Mekkes came to emphasis certain themes in a way that moved beyond Dooyeweerd’s articulation of his philosophy. Mekkes questioned whether it was correct to view the heart or religion as outside of time. He came to view the search for an Archimedean point beyond time from which a universal point of view may be obtained as too close to the neo-Kantian method (Mekkes 1973, 15). Such a method underplays the temporal activity of theoretical thinking and transforms it into a transhistorical point of view. Key to this criticism was Mekkes developing notion of cosmic time which also led him to suggest that Dooyeweerd had wrongly interpreted the order of creation as a static structure functioning as a framework for cultural development (Mekkes 1973, 68). He claimed that “Talk about ‘creational orderings’ as something in itself is … impossible” and so spoke instead of ‘structures under the rainbow’.

While being cautious about how reformational philosophy should understand the law-idea, he held on to the importance of its basic intension of opposing the dominant delusion of “autonomous” thought. The law-idea keeps the sense of non-arbitrariness of reality whereby being human is bound to an ordering that both precedes and succeeds its activities. Reformational philosophy in “rejecting every autonomy … follows the structures in the search for their meaning, a search not by the light of intellect, but with understanding under the light of integral truth through faith” (1973:61). Hendrik Hart interprets this theme as “a continued following of the disclosures of meaning which progressively becomes manifest in the experienced embodiment of the love of the crucified Lord. That is to say: in our embodied following, dimensions of God’s redemptive intent may on the one hand struggle to become manifest, while on the other hand they may remain hidden in a rigidly maintained earlier established order. Such following, for Mekkes, is a temporal motion which requires a continuity of reformation that cannot be given a priori boundaries. The order of reality must itself be reoriented to the manifestation of love in the cross, must itself be a developing order.” [2]

Influence

Mekkes influenced Johan van der Hoeven, Bob Goudzwaard,[3] Egbert Schuurman ,[4] M D Stafleu and P A Meijer .

Some quotes from Mekkes’ Dutch works

“It is for the covering up of ground motives, not for their content, that a christian philosopher must reproach his humanistic opponents.” (1961:35)

“In no way can man transcend his dynamic temporal existence” (1971:121)

“Right from the beginning reformational philosophy emphasized the dynamic character of creation as being God’s first revelation to the creature. That’s why it spoke of the ground-motive of creation.” (1973:58f)

“Talk about ‘creational orderings’ as something in itself is … impossible.” (1973:59-60)

“Rejecting every autonomy, she follows the structures in the search for their meaning, a search not by the light of intellect, but with understanding under the light of integral truth through faith” (1973:61)

Notes

[1] See Dooyeweerd’s comments in A New Critique of Theoretical Thought Vol. III p.426n

[2] “Notes on Dooyeweerd, Reason, and Order” in Contemporary Reflections on the Philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd Edited by Strauss and Botting p.135

[3] “The Dutch Calvinist philosopher, J. P. A. Mekkes, made me especially aware of the closed, autonomous world and life view that was and is still present in the positivistic, so-called value-free mainstream of economics”

[4] “The philosophizing of Mekkes was a constant inspiration to me as I worked on the philosophical elaboration of the central themes that are indispensable to reflection on technological development.” See Technology and the Future, p. 403, note 5

by Rudi Hayward

A full bibliography by A. M Pedersen and L. Derksen (Uitgave Filosofosch Institut VU, 1977) is available here. [pdf – off site]

Principal works

1940. Proeve eener critische Beschouwing der Humanistische Rechtsstaatstheorieen [The Development of the Humanistic Theories of the Law-State]. Utrecht-Rotterdam, 752 pp.

1961. Scheppingsopenbaring en wijsbegeerte [Creational-revelation and philosophy].

1962. “Wet en subject in de Wetisdee der Wijsbegeerte.” In Philosophia Reformata, pp. 126-190.

1965. Teken en Motief der Creatuur [Sign and motive of the creature].

1971. Radix, Tijd en Kennen [Root, time and knowing].

1973. Tijd der Bezinning (Time of reflection).

English Language Works

1955. “The Philosophy of Vollenhoven and Dooyeweerd.” The Calvin Forum, June/July, p. 219.

1956. “Some Comments.” The Calvin Forum, Jan, p. 74.

1964. “Introductory: The Transcendental Critique in the Field of Biology.” Philosophia Reformata 29, pp. 111-113.

1965. “The Transcendental Critique in the Field of Biology. Introduction to: J. J. Duyvené de Wit. A New Critique of the Transformist Principle in Evolutionary Biology. Kampen, Kok.

1971. “Knowing.” In Jerusalem and Athens: Critical Discussions on the Theology and Apologetics of Cornelius Van Til, edited by E. R. Geehan, pp. 306-319.

1973. “Methodology and Practice.” In Philosophia Reformata: The Idea of Christian Philosophy vol. 83, pp. 77-83.

2010. Creation, Revelation, and Philosophy translated by Chris Van Haeften. Dordt College Press.

2012. Time and Philosophy, translated by Chris Van Haeften. Dordt College Press.

Chronology of Johan Peter Albertus Mekkes (1898–1987)

Based on Stellingwerff in Biografisch lexicon voor de geschiedenis van het Nederlands protestantisme 6 (2006): 187-188.

1898 April 23 – Born in Harderwijk, the Netherlands.

Son of Jan Mekkes (teacher) and Antje van Vliet.

1915 Begins officer training in Kampen.

1920 Serves as officer in the 20th Infantry Regiment.

1923 April 13 – Marries Johanna Sophia van der Zee (1895–1980) in Groningen.

1927 Passes the state examination Gymnasium-A, prepared for through evening study alongside military service.

1928–1931 Studies at the Higher Military Academy (HMA) in The Hague.

1932–1935 Studies law at the Catholic University of Nijmegen.

1933–1940 Serves as adjutant to the Commander of the Field Army, Lieutenant-General Jhr. W. Röell.

1940 Earns a doctorate in law at the Free University of Amsterdam, supervised by Herman Dooyeweerd.

- Dissertation: A Critical Examination of the Development of Humanistic Theories of the Constitutional State.

- Completed three weeks before the German invasion of the Netherlands.

- Establishes reputation as a sharp legal scholar and Calvinist philosopher, deeply shaped by Dooyeweerd’s philosophy of the law-idea.

1942–1944 Prisoner of war in Germany, including detention in Neu-Brandenburg.

- Gives philosophy courses to fellow officers, among them M. R. H. Calmeyer.

1945 Works in political investigation following liberation.

1947 Appointed lecturer in Calvinist philosophy at the Netherlands School of Economics, Rotterdam.

1949–1972 Serves as special professor of Calvinist philosophy in:

- Leiden

- Rotterdam

1950 Appointed lecturer in constitutional law at the Higher Military Academy, The Hague (serves until 1972).

Formally joins the Walloon congregation of G. Forget in The Hague.

- Serves first as deacon, later as elder.

1951 Publishes the influential article “The Right of Resistance” in a Festschrift for H. Dooyeweerd.

- Sparks debate within the Anti-Revolutionary Party (ARP) over resistance in democratic contexts.

1956 Becomes honorary member of the national Societas Studiosorum Reformatorum (SSR).

1961 Publishes Creation, Revelation, and Philosophy.

- Develops the theme of history as the dynamic unveiling (ontsluiting) of creation.

1963–1972 Holds special professorships in:

- Delft

- Eindhoven

1965 Publishes Sign and Motive of the Creature, dedicated to Dooyeweerd.

- Explores the Christian foundational motive of freedom from worldliness, not from the world.

1960s Increasingly critical of:

- Synodical political pronouncements (e.g., nuclear armament)

- The ecumenical movement

- Together with other non-seceded Christians, seeks political affiliation with the Reformed Political League via the National Evangelical Association.

1965 Publishes “Le Temps” in Philosophy & Christianity : Essays Dedicated to Dooyeweerd.

1968 Receives the Festschrift Reflections from eight former students on his 70th birthday.

1971 Publishes Radix, Time, and Knowledge.

- Explores continuity between Greek dialectical motives and Renaissance/humanist philosophy.

1972 Retires from academic posts:

- Higher Military Academy

- Leiden, Rotterdam, Delft, Eindhoven

Ends service as church elder (early 1970s).

1973 Publishes final book: Time for Reflection.

- Emphasizes learning through love rather than theory, and the dynamic power of the Risen Christ.

1980 Death of his wife, Johanna Sophia van der Zee.

1987 July 26 – Dies in The Hague.